Dinner at Alinea, September 6, 2007

Alinea is in a more upscale part of town than moto, but that doesn’t mean it’s any easier to find. Spot the world-class restaurant:

If it hadn’t been for the valet sign, or knowing the street address of the place, we would have had no idea it was here. I guess if you don’t need casual foot traffic to fill your restaurant, why bother with street-level advertising?

The front door was opened for us, and we walked into a small hallway that looked like something out of Through the Looking Glass. It got shorter and narrower as we walked along it, and had a panel of antennae sticking out at odd angles at the very end. Just when I felt that I had to start ducking to clear the ceiling, two glass doors parted on my left, Star Trek-like, revealing the real entrance to the dining room.

We had miscalculated how long it would take to get to the restaurant, so we got there twenty minutes early. “No problem at all, sir.” They showed us right to our table, right by the shaded front windows. We were, in fact, twenty minutes early for a 6:00 PM reservation, so we had the dining room to ourselves for a while.

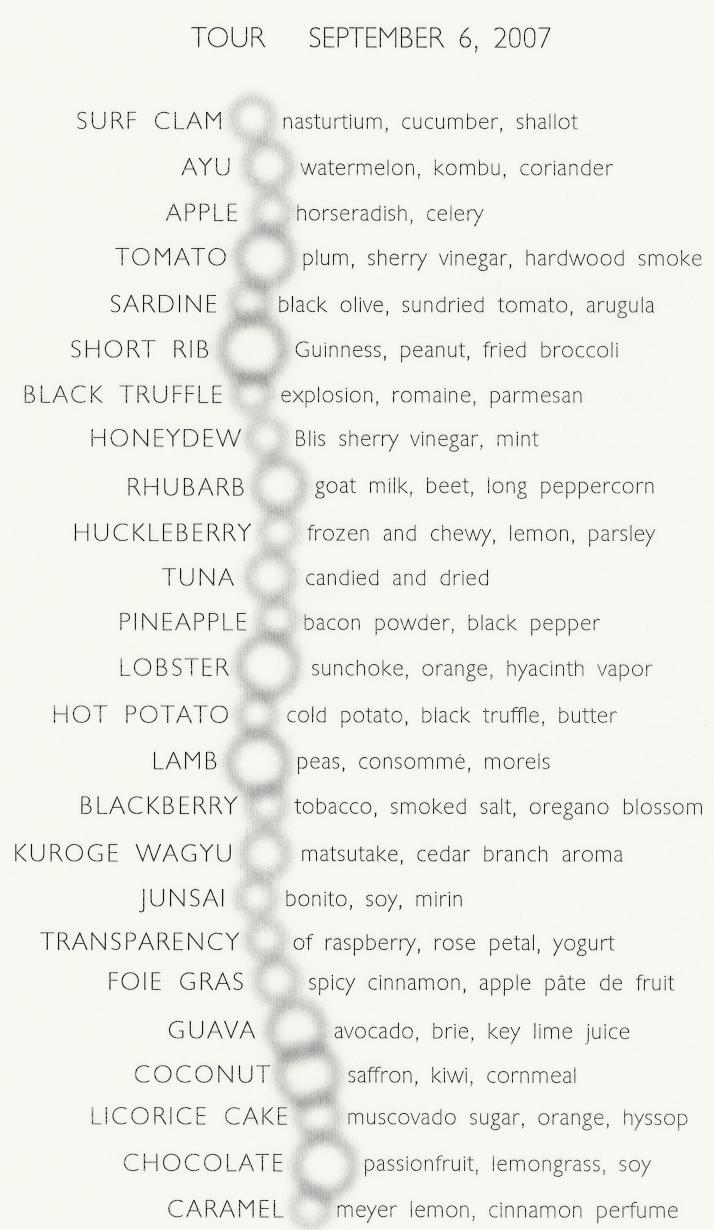

I had already placed our order three months earlier, when I made the reservation. The choice was between the 12-course tasting menu and the 24-course tour. Since I don’t get to Chicago often, the choice was clear; I had to go all-out. Once we were seated, our waiter confirmed that we were getting the 24-course menu, asked if there were any food allergies that they needed to know about, and, finding none, turned away to start the proceedings. I stopped him before he left, asking whether we’d have menus to follow along, because that had been the one real downside of elBulli for me. He said that they preferred not to, since they wanted to let the dishes provide maximal surprise. That was the reason I was given at elBulli, too, so that didn’t comfort me. After some pondering, he decided that he could give me something that would approximate the actual meal we’d be served, “but there will probably be some changes from this menu.” That was good enough for me. I didn’t look too closely at it, since I wanted to be surprised as much as they did, but it made me feel a lot better about the prospect of 24 courses.

Rather than flowers, candles, or a traditional centerpiece, our waiter brought out a couple odd-looking but attractive ornaments and set them on the side of the table: a pair of fresh cedar sprigs stuck into little metal holders, and a couple of key limes “shrink-wrapped” into plastic tubes.

We sat silently, in anticipation. Jesse channeled Morpheus from the Matrix, doing the “bring it on” gesture with a smirk on his face. Before long, the fun began.

The first course started unexpectedly, with the presentation of what looked like a monocle for each of us:

This turned out to be a silverware holder for part of the first course, which we were handed directly:

Course 1: “Surf clam / nasturtium, cucumber, shallot”

The bowl was unstable if set on the table with the fork mounted on it. So the “monocle” was a place to set the fork after eating the bite that was sitting on it; we were then to drink the soup in the bowl.

The forkful had a piece of surf clam, cucumber, lemon-shallot marmalade, nasturtium leaf, and nasturtium flower. It was an unexpected collection of tastes, fairly mild but enough to awaken my palate. In the bowl was a bit of nasturtium leaf soup; it was spicy like mustard or radish, but also played up the cucumber in the forkful.

After we finished, they cleared the bowls, forks, and monocles, and brought out the silverware for the next course:

They explained that they didn’t want to cover up their gorgeous mahogany tables with tablecloths (who can blame them?), but of course they wanted to keep the tables from getting dinged up by the dishes and utensils used to eat food on them. So they have various gadgets, such as the monocles shown above or these “pillows” for fresh silverware, to keep scratch-prone stuff off the tabletops. The pillows stayed on the table throughout the meal, and new silverware always got placed onto them. Not only did this avoid scuffing the table, it probably also made the waitstaff’s job easier, since the courses came on plates of widely varying sizes.

Course 2: “Ayu / watermelon, kombu, coriander”

This dish made it very clear, as if it weren’t already, that we were in the big leagues.

The Ayu, sometimes known as the “sweetfish,” is prized in Japanese cuisine. As the nickname suggests, it’s known to taste sweet, especially when served raw; some people think it has a hint of watermelon flavor. So Alinea went to town with this idea. We were served a piece of ayu (cooked), with a creamy mixture of Japanese barley and sesame underneath and a tile of watermelon under that. On top were some pieces of braised seaweed, the cooked (and edible) spine of the sweetfish, and some microgreen flowers. Alongside was a pool of sesame oil with spirals of liquid seaweed and the braising liquid. (Whew!)

And the fish was sweet! Not candy-bar sweet, obviously, just enough to get your attention. The watermelon matched the fish flavor very gracefully, and the sesame lingered for a long time. There were so many flavors and textures to absorb, and only three or four forkfuls to do it in, but they came together coherently to become a clearly Japanese dish.

This is as good a place as any to put in a disclaimer: I know there are parts of the dishes that I’m not remembering. My descriptions might look like I caught everything the waiters said about the courses, but that’s definitely not the case. The waiters’ memories were amazing, though.

Course 3: “Apple / horseradish, celery”

This was a bit hard to capture with my camera. It was brought out in a four-inch-tall glass with a thick bottom. We were told to take the whole thing in one bite, and to chew with our mouths closed, lest it get very messy. The ball was a hard but thin sphere of apple and horseradish, filled with apple juice, topped with a celery leaf, and surrounded with a strip of lime zest. It broke open easily with a crunch of the teeth, and released a flood of cold, thin apple juice. It tasted a bit like an apple-flavored Bloody Mary.

After this dish they brought out bread plates and butter. This being Alinea, it couldn’t be just any bread and butter, of course. The waiters brought out pieces of bread every few courses, different kinds every time, and the breads were supposed to roughly pair with the courses we were eating at the time. I fell behind on eating the bread, because I wanted to save space for everything else, so I can’t say how well they paired — but they were tasty. The butter was also something special:

The yellow butter was churned in-house, and was topped with black salt; the white butter was a goat’s milk butter from Quebec. The goat’s milk butter didn’t taste as “goaty” as I might have expected, but that’s probably a good thing. Both were very soft.

Course 4: “Tomato / plum, sherry vinegar, hardwood smoke”

We were apparently the first table to get this dish ever. It’s certainly tomato season in San Francisco, and apparently it is in Chicago too. The dish had many forms of tomato and hazelnut, including peeled yellow heirloom tomato on a spicy ketchup and hazelnut cream with Explorateur cheese. A poached plum sat in the middle. This was served on a pillow filled with smoke of applewood and peachwood:

The pillows were cloth, with (I would guess) a plastic bag with a few holes inside. The smoke leaked out of the inner bag slowly, and the weight of the plate helped push it out. The smoke was beautifully aromatic, but almost too much at first. I thought it really enhanced the tall, juicy piece of tomato at the back of the plate.

As the night went on, and later parties worked their way through the meal, it was fun to watch waiters striding quickly from the kitchen, bearing a tray with two or four absurdly large pillows on top. It could have been a scene in a fairytale or a Wodehouse novel. After the pillows were placed on their destination table and started leaking, we would eventually get secondhand whiffs of the smoke, reminding us of when we had that course. I enjoyed this experience all night long; since several of the courses were tiny, I didn’t have as much opportunity to savor them as I would’ve liked. Watching dishes go by and get described to other parties gave me a chance to think back over them and fill in the gaps in my memory.

Course 5: “Sardine / black olive, sundried tomato, arugula”

This was a tiny “timbale” of baby Japanese sardines, dehydrated, pressed, and formed into a ring. It was filled with a mousse of Niçoise olives, and topped with sun-dried tomatoes and micro-arugula. It was a single bite, about the size of a button mushroom. And it was potent, pure Provençal, like a pissaladière condensed into a mouthful, but not too salty and not unbalanced. Jesse was speechless for about 30 seconds after this one.

This was (apparently) the first of several appearances of special dishes and utensils designed by Martin Kastner for Alinea. This “pedestal” focused attention right on the little bite.

Course 6: “Short rib / Guinness, peanut, fried broccoli”

This was another whirlwind of flavors and textures. The brown square was a solid sheet of Guinness beer. On top of the sheet was a piece of beef short rib, shavings of broccoli, pink peppercorns, clusters of mustard seeds, toasted peanuts, and crispy fried tufts of broccoli. Underneath the sheet were purées of broccoli and peanut. The sheet was slippery-smooth, a striking and fun contrast to all the crunchy stuff on top of it. The flavors came together as unexpectedly Chinese, with the peppercorns and mustard seeds providing heat and the beef and purées giving richness. It was fantastically good.

Course 7: “Black truffle / explosion, romaine, parmesan”

A single raviolo, filled with black truffle “tea,” topped with a shaving of black truffle, caramelized romaine lettuce, and a sliver of parm. This was another one to be had as a single mouthful (no biting!) because of the liquid inside; it was served on its own spoon. There was no pretense of flavor balance here — just a one-note wallop of pure truffly goodness with an explosion of liquid.

Course 8: “Honeydew / Blis sherry vinegar, mint”

A cylinder of mint tea gelée, with a rolled-up slice of honeydew melon in the middle, and a couple drops of sherry vinegar inside the slice of melon. One small bite, but powerful contrasts: tender gelée, but crispy melon, and a light, cold, and fruity exterior against a pungent interior. Something (maybe the flower?) was distinctly salty, too.

I didn’t notice it at the time, since I was seated with my back to the window, but apparently at about this point in the meal the sun went down. Although the artificial lighting inside was good enough to make the transition subtle, the white balance on my camera sure picked up on it. Oh well…

Course 9: “Rhubarb / goat milk, beet, long peppercorn”

Several different forms of rhubarb. The first one had to be eaten very quickly, so I only got a blurry picture:

This was a ball of hot beet juice, in some thin wrapping, dropped into a glass of cold rhubarb juice. It was to be taken as a single shot. BAM! Not only tangy vs. earthy, but also hot and cold liquids in the same mouthful. Jesse said, “This gave me my first spine tingle of the night.”

As for the rest:

Left to right, we had: a crunchy “fruit roll-up” of rhubarb, a slice of rhubarb soaked in gin, with a juniper berry on top; rhubarb foam with citrus bits, served on a bay leaf; some crunchy gelatinous square of goat milk, with rhubarb gelée on top; rhubarb ice cream on top of hazelnut paste; and rhubarb jelly with fennel fronds and matcha foam. I especially liked the gin-soaked slice and the ice cream/nut paste for their intensity, and I was intrigued by the last one because it somehow came out tasting a bit cinnamony. The beet juice ball topped them all, though.

This course probably had more odd “utensils” than any other:

Course 10: “Huckleberry / frozen and chewy, lemon, parsley”

A piece of frozen huckleberry cake, with drops of lemon purée, parsley leaf, and parsley flower. It had frost (!) for “frosting.” It was really, really cold, but avoided being rock-hard; it was chewy like a caramel. I lost the pieces of parsley in my mouth, but Jesse said he bit down on them directly and definitely noticed. To give some perspective, the metal skewer used to pick up the piece of cake is the same size as the one in the previous dish, where it’s much smaller than the bay leaf.

Course 11: “Tuna / candied and dried”

A stick of “tuna jerky,” coated in the seasonings it was “cured” with: ginger, orange, hot pepper, and sesame. It had the texture of candied orange peel, and the pepper gave it plenty of heat.

This was finger food, so they brought out hot, moist towels to clean off with afterwards:

Course 12: “Pineapple / bacon powder, black pepper”

This was the tiniest course of all, about the size of a dime. Dehydrated pineapple and bacon powder were wrapped up in something pineapple-flavored. I don’t think it was actually mandolined pineapple serving as the “raviolo”; it was more like a fruit roll-up in texture. It was very bacony, and bits of the pineapple wrapper stuck to my teeth for several minutes afterwards.

Course 13: “Lobster / sunchoke, orange, hyacinth vapor”

One of the fancier plate arrangements of the evening. The outer bowl is filled with hyacinth blossoms and orange peel. Once the dish was presented, the waiter took a pitcher of boiling water and poured some into the outer dish, releasing the aromas of the flowers and the orange. Next, we were given a long thin skewer, with a cube of orange gelée and fennel flower at the end, and were told to eat it immediately, to prepare our palate for the rest of the course. The waiter stood there waiting for me to eat it so he could take the skewer, so there was no picture of that.

Finally, it was time for the actual dish: lobster, lobster mousse, sunchoke purée, fennel fronds, tarragon, and raw jicama. Sound good? This was not just one of the best foods that I’ve ever eaten, this was one of the best sensory experiences of any kind that I’ve ever had. It brought tears to my eyes. When cooking at home, I’ve imagined dishes that use two or three really flavorful, rich, luxurious ingredients, but I usually nix the idea, thinking “nah, the sum would be less than the parts.” This dish was of the same conception, but it didn’t hold back. The potent hyacinth aroma, the lobster, the tarragon, and the richness of lobster mousse were all potent on their own, but the combination was downright intoxicating. It was almost too much to take in at once.

Jesse said, “That dish reminded me of being high.”

Course 14: “Hot potato / cold potato, black truffle, butter”

A tiny bowl holding a cold purée of potato. Just above the “water line” of the soup, the bowl has a tiny hole with a metal skewer pushed through the hole. Suspended from this skewer are a chunk of hot potato covered with a shaving of black truffle and sea salt, a tiny cube of butter, and a tiny cube of parmesan. The side of the skewer that pokes out below the bowl has a little knob on it. We were instructed to pull the skewer by that knob all the way through the bowl, allowing the hot potato, butter, and parm to fall into the cold purée, then immediately down the whole thing as a single shot. The elaborate setup kept the hot side hot, and the cool side cool until the moment before I ate it, and like the beet/rhubarb ball in course 9, was a wonderful eye-opening experience. The potato and truffle combination is classic, and was focused into a single gulp.

Course 15: “Lamb / peas, consommé, morels”

Several forms of lamb (tenderloin, consommé) and peas (fresh, freeze-dried, and tiles of purée). The blobs in the upper-right hand corner were mint jelly (natch) and a yogurt-curry sauce. I didn’t exactly have much lamb growing up, so the mint jelly didn’t activate any food memories for me, but I really liked the yogurt-curry pairing with the lamb. Jesse said this course didn’t really do much for him; I enjoyed it, but not as much as some of the other courses.

Course 16: “Blackberry / tobacco, smoked salt, oregano blossom”

A cylinder of tobacco custard the size of two nickels, topped with a blackberry, oregano blossom, and smoked salt. Interesting, but it was there and gone in ten seconds. I couldn’t identify the tobacco flavor per se, since I don’t smoke. I was hoping it might give a nicotine buzz like the “Marlboro-infused coffee custard (with foie gras)” that Anthony Bourdain describes having been served at The French Laundry in his book A Cook's Tour, but I didn’t notice any of that either. Ah well.

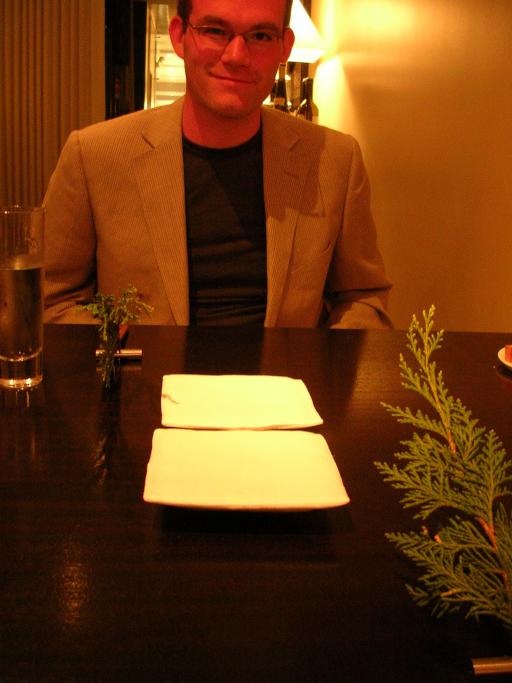

The waiter admitted at this point that one of the tableside decorations was not just another pretty twig, but was, in fact, part of the meal. After making sure that we were comfortable eating with chopsticks, he moved a metal cylinder and cedar sprig to the right of each place setting, and set a pair of wooden chopsticks on it.

Here’s Jesse anticipating the chopstickable goodness:

A couple minutes later, an insistent and growing sizzle on a tray from the kitchen announced the next course.

Course 17: “Kuroge Wagyu / matsutake, cedar branch aroma”

A solid stonelike plank, coated with popping and sizzling hot oil, held three one-bite morsels. Each had a beautiful cube of Wagyu beef and a pillow of matsutake mushroom duxelle, topped with leek blossoms and chives. The steak had already been cooked, so why serve it on a hot plank? Its real purpose, it turns out, was the hole at its far end. After setting the plank down, our waiter took the cedar sprig from the chopstick holders and stuck it into the plank’s hole. The heat of the plank, he explained, would release the aroma from the cedar and let it interact with the flavor of the meat and mushrooms. Here’s what the plank looked like after the course was done:

The plank didn’t work as well for me as I think it was intended to. The aroma wasn’t nearly as strong as the wood smoke in course 4, or even the sage utensils at moto. I didn’t want to lean too close to get a whiff, because Jesse got hit by a couple spatters of oil, and he confirmed that it was as hot as it sounded. Even without it, though, the course was fantastic. Matsutake mushrooms have a definite cedar and cinnamon flavor, so I can see why they wanted to pair them with cedar aroma. The smooth duxelle was full of matsutake flavor, and it went beautifully with the rich, melty, fatty beef. The heat of the plank seared the beef a bit more, giving it a crispy crust on the bottom.

Jesse was channeling Pulp Fiction after this course. “This one’s the madman.”

Course 18: “Junsai / bonito, soy, mirin”

After diligently wiping the spattered oil from the last course off the mahogany table, our waiter gave us a little something to clear the palate after the beef: a small glass of dashi holding a little sprig of junsai. What’s junsai? What, indeed. It wouldn’t be a true high-end meal without a little bit of something that many people haven’t seen before. Junsai, our waiter explained, is the sprout of the water lily, which forms a gelatinous “shield” around itself as it grows. It’s a delicacy in Japanese cuisine. I’ve certainly never seen it in any Japanese restaurant I’ve been to, though for example I haven’t been to Masa.

The rarity isn’t really the point, though. The dashi was cool and very full-flavored, and the junsai was … something else. It felt like a small, branched, soft twig, with a slippery coating that kept my tongue or teeth from getting too close to it, even as I teased it around in my mouth. It seemed to hang on to some of the dashi, so the flavor didn’t all run down my throat immediately. Quite a fun experience.

Course 19: “Transparency / of raspberry, rose petal, yogurt”

A “scarf” of rose and raspberry, sprinkled with yogurt powder. The metal contraption that held it showed it off nicely, and kept our fingers from getting sticky when eating it. By pinching the bottoms of the two disks together, the tops came apart, releasing the last bit of the dish. I thought immediately of my girlfriend Rachel, who couldn’t come to Chicago for these meals, but was with me at elBulli when we had the beetroot bows with vinegar powder. She still sighs when talking about that piece of work, and she reacted the same when she heard about this one.

A gift from the chef: “Foie gras / spicy cinnamon, apple

pâte de fruit”

This can’t be an official course, naturally, because it’s illegal to sell foie gras in Chicago. But this was “a gift from the chef!” A cinnamon meringue puff, with a hole on the underside filled with apple jelly and a tiny bit of foie gras mousse. The foie taste only came out after 10 or 15 seconds, subtle but unmistakable. Jesse deemed this one “a fuckin’ work of art.”

Course 20: “Guava / avocado, brie, key lime juice”

Dessert is definitely underway here, with this first of three raucous multi-flavor dishes. This one started with a dollop of guava foam and lime zest, a tile of avocado and brie semifreddo topped with basil ice, a sweet pine nut croquant and a sugar-coated piece of Brie in front, and a ball of rum and brown sugar in back. The waiter then took the remaining tableside decorations (the “plastic-wrapped” key limes), punctured them with a clever gadget, and squeezed them with a big pair of pliers; the plastic wrapping around the lime channeled the juice down onto the semifreddo. Finally, he anointed the center part with a pour of guava soda.

I’m really excited to see desserts like this which explore unexpected sweet flavor combinations. It’s become a cliché that many “nice” restaurants (at least in San Francisco) have the same five or six things on all of their dessert menus. Sure, I’m a sucker for an occasional molten chocolate cake, but come on! Dishes like this one show just how much culinary ground is still open for exploring. In fact, there was so much going on here that I can’t describe it all. The highlight for me was the contrast between the intensely cold and slightly savory basil/avocado/brie tile and the tang of the guava and lime juice. Jesse thought the rum ball was “out of control”; it was another liquid-filled ball that exploded in the mouth.

Jesse got macro-mode working on his camera by this point, and got a couple of beautiful close-ups:

Course 21: “Coconut / saffron, kiwi, cornmeal”

Another exploration of sweet flavors. A soft sheet of coconut purée was draped over pieces of cornmeal pudding, kiwi, and corn leaf gelée. The gelée tasted like the scent created by shucking a fresh ear of corn. On top were sprigs of cilantro and saffron, cubes of some other cornmeal preparation, and shards of dehydrated coconut. This was yet another amazing mix of texture and flavor contrasts; the cubes of cornmeal on top were wonderfully chewy. The whole thing was toe-curlingly good.

Here I am, trying to take it all in and wishing there had been just a bit more.

Course 22: “Licorice cake / muscovado sugar, orange, hyssop”

The next course was a one-bite morsel served on an antenna. This device put the food right at mouth level, which was the idea. It was to be eaten without using hands; just stick it in the mouth and pull it off.

The main “block” was a frozen licorice purée surrounded by licorice spun sugar. Down the antenna from this were a cube of muscovado jelly and a sprig of anise hyssop. When I bit down, I understood why the antenna was useful: it kept the tiny cube and the sprig toward the front of my mouth, so they didn’t get lost among the richness of the purée or the shardlike texture of the spun sugar. Another very intense mouthful.

Course 23: “Chocolate / passionfruit, lemongrass, soy”

An aggressive push into savory flavors. The long brown “snake” was a ganache of Ocumare chocolate, wound around a passion fruit noodle on one end, with pieces of candied orange and herbs scattered along it and a lump of lemongrass ice in the lower left. This was contrasted with several forms of soy sauce: a lump of soy jelly on the left, a few patches of soy “marshmallow,” and a pinch of soy powder on the right. The soy forms were awkwardly salty on their own, but were tempered by the sweet flavors. It was an interesting contrast, but not really my thing. I didn’t leave a drop of the Ocumare ganache behind, though.

Here are close-ups of the two ends of the ganache “snake”:

Course 24: “Caramel / Meyer lemon, cinnamon perfume”

A sweet note to finish on. A preserved Meyer lemon, coated in caramel, tempura-fried, and sprinkled with cinnamon, served on a cinnamon stick. I wished there had been more Meyer lemon flavor, but I enjoyed it for what it was — basically a gooey donut hole.

Here’s a broader view of the squid it was served with:

And here’s the menu that we received at the end of the meal. The circles aren’t just decoration; they actually add quite a bit of description. The size of the circle indicates the size of the course; the darkness of the circle suggests how strong the flavors were in the course; and the left-to-right positioning of the circle shows where the course lies on the savory-to-sweet spectrum. Edward Tufte would be proud.

It seemed like we flew through the meal, but at the same time, when we saw early courses get served to other tables later in our meal, it was like they were from another day. It turned out that I didn’t really need the menu that they’d given me at the start of the meal — the courses were smaller than those at elBulli, and the pacing was calm, so I left feeling full, but not uncomfortable. More importantly, though, I thought of a quote from Dornenburg and Page’s Culinary Artistry, where they compared how people felt after finishing a meal. After finishing a fast-food meal, you might say “I’m full”; after a nice meal at a sit-down restaurant, “that was delicious”; after a transcendent meal, “life is wonderful.” As I walked out of the restaurant, the last line stuck with me. Life is wonderful.

Conclusion

I’m really glad I had both this meal and the one at moto.

Both restaurants demonstrated a wide range of new sensory experiences: temperature contrast, nontraditional “cooking,” use of aroma, and new forms of well-known ingredients. Both paid careful attention to plating and presentation. Both meals were well paced, allowing digestion but not boredom: the meal at moto took 4½ hours, and the one at Alinea took 5½. Neither was cheap as meals go ($165 at moto, $195 at Alinea, plus tax, tip, and beverage), but both were remarkable in delivering as much as they did for that amount of money.

I’m also really glad I had the meals in the order I did. If I had tried the restaurants in the opposite order, I suspect I might have dismissed moto as a slapdash attempt to do what Alinea was doing. But as it was, I had one “fun” treatment of molecular gastronomy and one “haute” treatment.

moto is clearly proud of their kitchen technology. Our meal had at least five courses which had an ingredient prepared with LN2, and Jesse (who’s a postdoc in neurobiology) recognized the sound of liquid nitrogen being transferred out of a dewar, which escaped from the kitchen at some point. As a Techer, I have some fondness for wacky stuff done with liquid nitrogen.

But you don’t have to be a nerd to enjoy what moto is doing. Their general attitude seems to be “see what fun and wonderful stuff we can do to food using technology.” Part of this playful attitude is reflected in the atmosphere of the dining room, which is more relaxed in a lot of ways: jacket not required, odd background music, chattier waitstaff. And over half the courses were blatant references to casual American food! The sensory illusion of seeing familiar food in an unexpected context kept us intrigued throughout the meal.

Alinea aimed for a five-star meal, and I think they delivered. The waitstaff was calm, attentive, and fiendishly competent. The plating showed a French Laundry-level attention to detail. The courses showed a reverence for the “technological magic” that Nature has worked over millions of years of evolution, from the solitary blackberry to the sweet ayu. (In contrast, moto’s heavy use of flavoring powders seemed kinda austere.) Several dishes had clear references to other cuisines (Japanese, Provençal) or classical flavor combinations (lamb and mint jelly), while many others were brand-new to me.

Beyond all that, though, the biggest difference was that Alinea used creativity and technical virtuosity to make food that engaged all my senses and my emotions. Seeing the familiar in a new context is fun; seeing the unfamiliar, and having it amaze you over and over, is something else entirely.

To draw the other inevitable comparison, how did these meals compare to my one meal at elBulli?

First, I wouldn’t compare moto and elBulli. Even setting aside the food, the atmospheres of the meals were completely different, and that alone makes it very hard for me to compare them. Alinea and elBulli were much more similar experiences, though. I think elBulli pushed the envelope a bit farther, and their attempts to “do nature better than nature” still astound me. On the other hand, Alinea’s meal was more reasonably sized and paced, which was the one significant flaw of my meal at elBulli, and it was much, much easier to get a reservation. So while I think elBulli remains the better meal, Alinea was the better experience.